Thus far, the response to Project NO MAN’S LAND has been extremely positive.

Which means, we have a green light to continue forward.

There is no real method in my madness when it comes to the order in which I am presenting my linear pairings. Ultimately, it all depends on my mood and what varietal and style I feel most inclined to write about at that particular moment.

My recent preoccupation with Asian and Thai foods has put me on a mission to find their perfect beverage counterparts. Gewürztraminer is often hailed as one of the few wines suitable for drinking with Asian cuisine. After some brainstorming, research and help from a friend — I decided that the Belgian Witbier was a sufficient linear pairing for the Gewürztraminer.

And this is why …

THE VARIETAL: Gewürztraminer

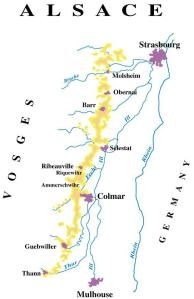

The name Gewürztraminer originated in Alsace, France and literally translates to “Perfumed Traminer.” The varietal belongs to the “Traminer” family, which is often referred to as a family of clones. This is where half of its name comes from. The other half of its name – “GEWURTZ” – refers to its aromatic & spicy nature.

The history of the Gewürztraminer is complicated and rather confusing (if I do say so myself). Although its name is German, its roots are Italian. It is a mutation and distant relative of the ancient Traminer varietal, a green-skinned grape that originated in the northeastern region of Alto Adige, Italy.

At some point, the Traminer varietal mutated into dark pinkish-brown, spotted berries. It most likely under went a musqué (‘muscat-like’) mutation, which ultimately led to the extra-aromatic Gewürztraminer varietal. Like the Pinot Noir grape, the Gewürztraminer is a very fussy and obnoxious varietal. In order to produce great wine, it demands a very particular soil and climate.

Depending on the fruit ripeness, the dark pink color of the Gewürztraminer grape produces wines that are light to dark golden-yellow in color with a slightly copper tone. For a white wine, Gewürztraminer is as full-bodied as they come (but not necessarily as full-bodied as most reds). It is infamous for its strong, heady and perfumed aroma and its exotic lychee-nut flavor.

In Europe the grape is grown in Italy, France, Austria, Bulgaria, Croatia, Hungary, Luxembourg, Moravia in the Czech Republic and Slovakia. In the New World, the grape is perhaps most successful in New Zealand and in the far south of Chile but is also produced in several regions throughout the United States.

The best wines produced from this varietal are, by far, from the Alsace region of France. “Classic renditions of this grape have the aroma of banana when young and only develop a real pungency of spice in bottle, eventually achieving a rich gingerbread character when mature.” -Sotheby’s Wine Encyclopedia.

Because of its overly potent and spicy nature, the Gewürztraminer varietal is one of the only wines commonly paired with Asian food (especially spicy). It is also an excellent match for cheese (both soft and strong/aged), Chinese food, cinnamon, curry, duck, fruit (definitely tropical), ginger, ham, Indian food, sausage, smoked food, spicy food & Thai food.

Enough about the wine … let’s talk about the beer now, eh?

THE STYLE: Witbier

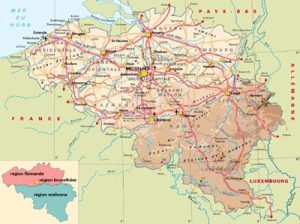

Witbier, called “Biere Blanche” in French, is the Flemish word for wheat beer. It was once the dominant style in the area east of Brussels. Specifically, it originated in the village of Hoegarten in the city of Louvain.

As a result of its relatively high protein content, this style of beer is typically extremely hazy. Although the name suggests that the beer is made solely from wheat, it is actually produced with at least 50% malted barley. As with most styles of beer, the Witbier recipe varies with brewer preference. Traditional recipes use around 54% malted barley, 41% unmalted wheat and 5% unmalted oats.

The Witbier style is always spiced, typically with coriander and the peels of both sweet and bitter oranges. Brewers frequently use at least one additional “secret spice” — known only to the brewer and the brewer’s “herb merchant”. The element of spice in Witbiers is the main factor that differentiates it from most other styles of wheat beers as well as one of the primary reasons why I think that the Witbier style of beer makes an ideal linear pairing for the Gewürztraminer varietal of wine.

Witbiers are traditionally produced with two entirely different types of orange — sweet & bitter. The sweet orange, available as dried peelings, is no different from the standard grocery store orange. The bitter, or Curacao orange, is very accessible in Europe — yet difficult to find in North America.

In addition to being “spicy”, Witbiers tend to be slightly sour due to the presence of lactic acid. They are very VERY lightly hopped (usually less than 20 IBUs – International Bittering Units). Other typical, yet less noted, descriptors include banana and clove (the typical aromas yielded by Belgian yeast).

The Belgian Witbier is very similar to the Gewürztraminer in that it also pairs exceptionally well with Asian food as well as Indian food, Thai food, curry, pork and many cheeses. Both are notorious for being “spicy” beverages and both are commonly paired with spicy dishes. In addition to sharing “spicy” qualities, both are similar in body, texture and mouthfeel (and at times, even color).

As with the previous pairing, I would love to hear feedback on this post. Hit … or miss?

Cheers!

This was not only a great read, but it was also very informative (not to mention you hit on one of my favorite types of food as well as a great varietal)

I really like the concept behind this series and can’t wait to read more!

Which beer would you pair with a late harvest Zinfandel?

Cheers!

Beautifully presented, intelligent yet not cerebral, enjoyable, and well researched. Bravo. Did you reach out to the Asian community with this?

Interesting idea but misses the mark in some respects. Although it’s “common wisdom” that Gewurz and spicy food pair well, reality often shows otherwise. Gewurz’s low acidity, relatively high alcohol and natural astringency frequently clash with Asian cuisine. The abundance of heat spice, salinity and umami work to exacerbate Gewurz’s astringency and alcohol. With little acidity to compensate, it’s even worse.

While there are superficial similarities, beer lacks the food compatibility of wine…texturally it can’t compare and it usually, but not always, has a magnitude of pH higher than that of wine (in fact, Witbier tends towards high acidity for beer and Gewurz has unusually low acidity for white wine, making the comparison even less cogent). Bitterness accumulates on the palate, particularly in the absence of acidity. As such, naturally bitter foods make a beers bitterness worse and vice versa. It’s interesting to compare beer to wine for flavor and texture reference but for pairing purposes the comparisons usually fall short.

I’d like to see you pair a range of beers with known acidity and alcohol with foods of varying acidity, sweetness and bitterness. Be the first to establish some standards of what works and why.